Progressive reflections on the lectionary #86

Monday 13th October 2025

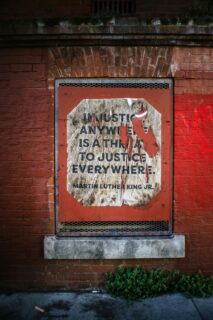

Luke 18:1-8 A story about non-violent resistance, resilience, and hope

A widow repeatedly petitions an unjust judge until he finally gets fed up and grants her the justice she requests - in a satirical little story about the conditions the poor faced in his time, Luke has Jesus tell his disciples to remain open to the divine and to give an example of the power of resilience. More than a story about individualistic, transactional prayer, this is an object lesson in how to survive in a time when expectations of Messianic return were crumbling and injustice was a daily experience.

It’s helpful, perhaps, to take a couple of steps back before jumping into this one.

First we should take a step back to recall that Luke was writing some decades after Jesus had been crucified.

Then we should take another step back to recall that the expectation was that Jesus would fulfil the role of the Messiah (the Christ) - the promised leader who would restore the fortunes of the Israelites.

Surely, the Christians of the first century CE thought, death could not contain this promised one? Surely he would return? And surely that would be…well… soon? As the years advanced, the expectation of this return must have been slowly ebbing away. By the time that Luke was writing, it was necessary for community leaders to find ways of encouraging their members not to give up hope of the arrival, or revelation, of God’s kingdom.

This story comes from a section in Luke that deals with precisely this issue. In chapter 17 the writer has the Pharisees ask Jesus ’when the kingdom of God was coming…’ A good question, given it’s evident failure to materialise.

Jesus gives an unusually gory (and symbolism laden) answer that concludes with the apocalyptic line: “Where the corpse is, there the eagles will gather.” A template, perhaps, for Eric Cantona’s famous quip about the seagulls and the trawler before the press back in 1995.

So we skip forward in this discourse about ‘when on earth will all this end?’ to this story about a widow who keeps appealing to the judge until he gets so worn down that he grants her plea for justice.

There was no middle class in that society - there were the doers and the done to. Here we have a judge who represents the powerful, and a widow who in this case represents the powerless. Or the apparently powerless, anyway.

The author introduces the story with the following line:

“Then Jesus told them a parable about their need to pray always and not to lose heart.” Luke 18:1

I think it’s unhelpful that the two ideas here are often run into each other. This is generally based on a transactional understanding of prayer (‘keep asking until you get what you want,’) rather than a relational one (‘maintain a posture of openness to the leading of the divine.’) It’s no surprise that, as a process theologian, I favour the latter.

In any case, the Greek word for ‘to pray’ here: προσεύχεσθαι (proseuchesthai) is a rich word which carries with it indications of posture, intimacy and involvement. We lose a lot of its power by simplifying it and turning it into something which is the equivalent to ‘asking’ - we need to recognise it’s formational power.

“Pray always” indicates that we must always be ready to listen, to participate in the life of God’s kingdom - to let prayer shape us - not that we should simply keep asking for what we want. After all, that was directly opposite to the way that Jewish teachers taught about prayer - ‘don’t weary God with repeated supplications’ was the main view.

So the first point is ‘remain open to God’ - keep praying. But the bulk of the story is about resilience.

This was a key message for the people of the time - the importance of ‘not losing heart’ despite the evident problem of the lack of a returned Messiah.

So here the figure of the widow becomes the key character, as Jesus pokes a bit of satirical fun at the figure of the judge - a symbol of the injustice of the time.

We limit the power of the parable if we look at it through an (anachronistic) individualistic lens. It’s not really about one woman and one man - they are symbols. This is a story about the importance of resilient resistance in the face of oppression and marginalisation.

Simply put, it is resilience that allows some people to cope in difficult situations better than others. The widow, who in this story embodies the vulnerability of the marginalised, demonstrates such resilience in the face of an apparently hopeless position.

There’s no reason to expect a good outcome for her, and yet eventually her non-violent protests pay off. It is a simple truth that this such resilience is even more effective in a group, a group like those early Christians. So here the writer we call Luke is motivating his community to keep going - ‘don’t give up’. He doesn’t discuss prayer, he doesn’t give instructions about how to pray, instead he encourages an ongoing openness to divine leading, and to continue to fight (in a non violent way) for justice even when the situation seems entirely hopeless.

By remaining open to the leading of God, and by refusing to give up in the face of a culture which would deny even basic justice, the first listeners are encouraged that they will, yet, see the kingdom of God.

The passage ends with a question:

“When the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on earth?” Luke 18:8

Rather than a piece of rhetorical despair we should see this as a provocation, a challenge. Remember that ‘faith’ (pistis) is about faithfulness, loyalty to purpose (like a mustard seed). It has nothing to do with doctrinal assent, it is about active, resilient, enacted trust. If the Messiah turned up today, would he find anyone who has remained loyal to the upside down ways of the kingdom? It’s a good question.

This blog is taken from Simon's Substack email series, to subscribe please go to https://simonjcross.substack.c...

Image: Photo by Jason Leung on Unsplash

Comments