Progressive reflections on the lectionary #62

Monday 14th April 2025

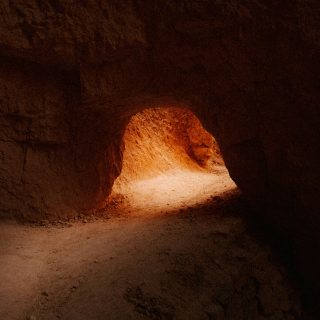

Luke 24:1-12: The empty tomb

There are two dominant traditions about what happened in the aftermath of Jesus’ death in the early Christian writings. Effectively they comprise the ‘appearances’ tradition, and the ‘disappearance’ tradition. The latter first crops up, for us, in the gospel of Mark where we learn that Jesus’ body, buried after his execution, was found to have disappeared.

For Mark, the earliest gospel writer, it is the disappearance tradition which is primary - original endings for Mark have the book complete at verse eight with the silence of the women who found the tomb empty. (Later addendums top Mark’s account up to allow his account to mesh more naturally with the appearances tradition.)

The other earliest accounts, found in the writings of Paul, focus on the appearances and don’t really consider the disappearance - there is no explicit mention of an empty tomb. Some suggest that the ‘disappearance’ tradition is a female centred one, while the ‘reappearances’ is a male one. This may be an oversimplification, but it is worth considering.

By the time we get to the gospel of Luke, which provides our lectionary gospel passage for Easter Sunday, we’re on the way to a conjoined tradition. In this particular passage, though, we’re still squarely in disappearance tradition territory, a missing body, an open tomb, and two mysterious figures in ‘dazzling clothes’ who act as the requisite witnesses of what has taken place.

Luke either improves on Mark’s rather problematic version of the same story, or uses a different source altogether: he has different women, a different timeline for anointing, different wording and then, of course, a rewrite of the ‘silent’ women which, crucially, allows them to tell others what has happened. In doing so he presumably uses some of the coexisting oral traditions to smooth out the discrepancies found in Mark’s telling.

Such editorialising has continued so that now, like Christmas, Easter is sometimes told as a composite story, with aspects cherry picked from different (and conflicting) gospel traditions which, taken together, form a rich ‘whole’ full of drama and symbolism. What this does, though, is conflate the two traditions (disappearance and appearance) and thereby combine the idea of absence with that of presence. Jesus, in these conflated stories is simultaneously absent and present in both physical and symbolic terms.

I’m not saying there is no value in doing this, but part of the power of the disappearance tradition, though, is that it doesn’t rely on the physical presence of the man Jesus for legitimacy. We are not required to accept that a corpse was revivified instead we are asked to sit with the profound challenge of that absence and what it might mean for us.

Ultimately I think it is absence, rather than presence, that invites a ‘spiritual’ response. Jesus’ mission remains unfulfilled, are we willing to commit to continuing it? Are we willing to resist the powers of empire in our own lives and communities? Are we willing to endeavour to do what is ‘right’ despite the lack of the sort of physical proof that this will all work out ok?

Christianity is often mocked (with some justification) as ‘pie in the sky when you die’ - but the foundational disappearance/absence tradition doesn’t offer that. It reflects the savage reality that following the Jesus way remains hard - it asks us to consider if we are, ultimately, genuinely willing to walk the narrow path wherever it may take us and then says that when we do - there is ‘Christ’.

“Why do you look for the living among the dead?” The women are asked. It is in that moment we have moved beyond Jesus the man, to the hope of something transcendent - that the longed for Christ, the saviour of the Jews is not found in a body, but in the life of the community. It is something much greater than one person: Christ is now found in the love and service shared among those who continue to follow the Jesus way.

Part of the power of the disappearance/absence tradition is that it calls us to look within. Not into the tomb, not beyond the realm of life, but into the life of the wider community, into the Church (in its fullest understanding). It is by taking the disappearance of Jesus into the here and now that we can more meaningfully meet the appearances/presence tradition. Not in the seeing of ghosts or reanimated bodies, but in the recognition that where the work continues, and wherever people come together to enact the values which proclaim ‘the kingdom of God is here’, there we find Christ.

This blog is taken from Simon's Substack email series, to subscribe please go to https://simonjcross.substack.c...

Image: Photo by Cody Hiscox on Unsplash

Comments